From Dan Vogel:

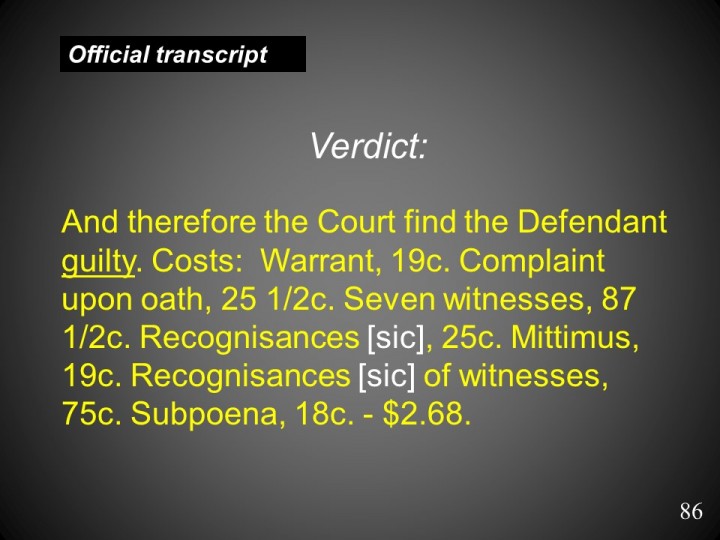

Bainbridge resident Abram W. Benton claimed in 1831 that Smith was “condemned”, but “considering his youth, (he then being a minor) and thinking he might reform his conduct, he was designedly allowed to escape”.[40] It is unclear if Benton had attended the 1826 proceedings, but in bringing a warrant against Smith on the same charge in July 1830 Benton demonstrated that he was familiar with issues of the first prosecution.[41] In an 1842 statement, Joel K. Noble, the Colesville justice before whom Smith would appear in 1830, also said Smith had been “condemned” in 1826 but that “whisper came to Jo. off off” and so he “took Leg Bail.”[42] In other words, someone suggested to Smith that he jump bail and leave town. If so, this would explain why a Court of Special Sessions was called but not held in Smith’s case. However, Smith’s subsequent return to South Bainbridge, first about November 1826 seeking employment with Stowell and again in January 1827 to be married by Justice Tarble, suggests that there was more involved than Smith’s escaping custody. If Smith had escaped custody, it is unlikely that he would have returned to South Bainbridge.[43] I suggest the following scenario:¶14 At the conclusion of the examination, Neely released Smith on his own recognizance to appear at the forthcoming trial. But when he learned that Smith had unlawfully crossed the county line into Colesville, presumably to the home of Joseph Knight, Neely issued a Mittimus to have Smith taken into custody and brought back to South Bainbridge. Constable DeZeng then traveled “10 miles…with Mittimus to take him”.[44] Upon being returned to South Bainbridge, Smith managed to work out an off-the-record agreement with Neely. Smith had good reason to negotiate since it was becoming increasingly clear that his defense had no legal basis and that a formal trial could result in his conviction and imprisonment. Smith’s youth (being nine months short of his twenty-first birthday), and Smith’s seeming willingness, although unrepentant, to abandon his treasure-seeking career may have inclined Neely toward leniency.¶15 In addition to quitting scrying for treasure and lost objects in South Bainbridge, Smith may have agreed to leave town for a specified length of time. In misdemeanor cases, justices had power “to impose a fine not exceeding twenty-five dollars, or imprisonment in the common gaol of the county not exceeding six months, or both, as the case may require.”[45] In misdemeanor cases involving nonresidents of the county, the same statute stipulated that upon payment of the fine and/or release from prison, the “offender shall be immediately ordered or transported out of the said county to his last place of settlement or abode if known; and if any person so ordered or transported shall remain in the said county for forty-eight hours, or return thereto within six callender months after such order or transportation, he shall be again fined as aforesaid, or confined as aforesaid …”[46] Neely could have insisted that his nonresident defendant leave town for the stipulated time. So when Smith returned to South Bainbridge eight months later, there was no worry of arrest as long as he did not engage in scrying. Unaware of the off-the-record agreement, many of the townspeople probably assumed Smith had escaped custody.¶16 Although the documents leave some things to conjecture, they uncover evidence enough to render Oliver Cowdery’s 1835 claim that Smith had been “honorably acquitted”[47] indefensible. Ultimately, however, conclusions about innocence or guilt are not as enlightening to historians as descriptions from reliable witnesses who have recounted Smith’s early methods of operation as a treasure seer. As Dale Morgan concluded: From the point of view of Mormon history, it is immaterial what the finding of the court was on the technical charge of being ‘a disorderly person and an imposter’; what is important is the evidence adduced, and its bearing on the life of Joseph Smith before he announced his claim to be a prophet of God.[48]